Books - Read and Enjoyed

The Dawn of Eurasia

Penguin, 2018

by Bruno Maçães.

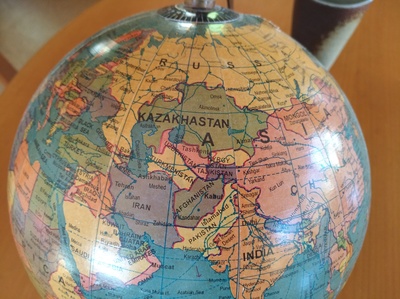

The focus of this book is the diversity and unity of the continent Eurasia and the author’s thesis is, that the world politics of the next decades will be defined by what is happening on that continent, and that it is best understood by looking at Eurasia as a whole, rather than at any of its regions in isolation. Maçães very much agrees that the continent is diverse and even that no convergence is in sight, but he contends that the political dynamics is best understood by considering how the main regions interact with each other. It is the system, consisting of diverse parts, that determines the development, not any of the main players by itself, because none of them is expected to dominate in the foreseeable future.

For a popular politics book the technique of narration is unusual. Rather than presenting a thesis and marshaling the arguments in favor, the book is structured as a traveling report. Maçães seems to be a diligent traveler who takes his time to indulge into the local culture and interact with whoever he happens to meet. His itinerary starts at the center of the continent, in Azerbaijan and the Caucasus, where he finds that the division between east and west, Europe and Asia is not perceived as such because the region has always been exposed to influences from all corners of the continent. Throughout the long history of the region, peoples have moved through, conquerors have invaded, great empires have emerged and vanished. The population is very diverse tracing its origin to remote places to the south, east and west. The region around the Caspian see seems always to have been connected to the steppe peoples to the east and as far away as China, to India, the Persian and Arabic cultures to the south and Europe to the West.

Maçães continues his trip eastwards through Kazakhstan, who perceives itself to always have been in the center, to Khorgas at the Kazakh-Chinese border. Khorgas is a quickly growing trading city that plays an important role in China’s road and belt initiative and links Xinjiang to Kasakhstan, China to Pakistan and eventually Europe. The Road and Belt is a huge infrastructure program that attempts to coat Eurasia with rail and road connections, with ports and trading posts, with pipelines and power lines, that will eventually pull the continent ever closer together. Europe and China two of the three biggest economies are located at opposite ends of the continent, are drawn to each other with inescapable attraction, even though their perception and understanding of themselves, of each other and the world could hardly be more distinct.

Maçães view is that China has a long term strategy, which is politically motivated and with the objective to increase its influence and safeguard its development, minimize external constraints and maximize its independence and its set of options. Europe is slow to respond to this challenge because it relies almost exclusively on a rule-based approach that fails to constrain others but constrains itself to the point, where it can make hardly any decisions anymore, even when quick and bold actions are urgently needed. Europe’s rule based approach works when it deals with partners that are weak and strongly attracted to Europe like the countries in Eastern and southern Europe. But it fails when faced with other strong actors that refuse to negotiate rules and, most importantly, refuse to be constrained by rules, like Russia and China.

Historically all civilizations and countries on the Eurasian continent were faced with the Western Question. When Europe set out on the path of modernization a few centuries ago, its technological prowess and organizational skills soon surpassed all its competitors on the continent and each country, Russia, Japan, China, India, Persia, Egypt, etc. had two choices which were hotly debated in each of those and many other countries around the world. Should they look back at their own history, identify the core strength of their civilizations, cherish and develop them to face up to these aggressive Europeans with their superior military technologies? Or should they learn from the aggressors, find out what was their secret, adopt some or most of the foreign customs and culture, like science, education, religion, political organization, business practices, and so own, to stand a chance in the competition? Each country labored with this question under great pains and came up with its own peculiar set of solutions, which in most cases had to be revisited and revised after it failed. Some countries have been successful in finding a working model relatively quickly, like Japan, for others it took a century longer, like China, and many other are still not content with the answer to this question they have found and tried.

After having visited China and considered briefly India’s growing role at the southern edge of the continent, Maçães turns his steps and attention towards Russia. For several centuries Russia has given different answers to the Western Question. It has sometimes tried to learn from Europe, adopt its culture and thinking, and catch up with Europe’s fast progress in science and technology, only to move away again like a huge pendulum, putting itself into the opposite position, assert its own history and culture, and accentuate the differences rather than the shared traits. Today it faces two formidable neighbors in China and Europe, the former becoming more assertive and self-confident by the day due to its exponentially growing economic clout and intimidating population size. The latter, even though its peak of influence and power has passed long ago is still convinced of its superiority, has three times Russia’s population size and four times its economy. This leaves Russia in an unpleasant situation, squeezed between two bigger neighbors, both overly self-confident and economic and demographic trajectories developing to their advantages. But Russia has a vast landmass, is strategically well positioned, commands enormous natural resources and will benefit from climate change in contrast to its neighbors to the east, west and south. Most importantly, its mind set and view upon the world is poorly understood by its neighbors, in particular its neighbor to the West. In contrast to Europe, Russia has little interest in a stable, predicable state of affairs. It prefers high dynamics and rocky developments, because it expects more opportunities and benefits at the boundary of chaos. The Russian state and its president interact with their partners and foes, just like they deal with their own population. They have no interest in stable, reliable rules but prefer to surprise others, break the rules and inject chaos in well measured doses.

Returning to Europe Maçães muses that Eurasia’s once dominant region becomes more and more the object of politics and the victim of developments because it abstains from asserting influence on the other parts of the continent. As it foregoes a more active role it becomes increasingly passive and constrained. Since its rule based approach does not really work with the likes of Turkey, Russia or China, it becomes defensive and disconnects politically. This approach is bound to fail as the war in Syria, the migrant crisis, the financial crisis, and essentially any other crisis demonstrate that emerge somewhere on the continent.

The sole super power is curiously absent from this contemplation about current and future world politics. Only in the epilogue Maçães turns his attention to America. He does not deny that the USA is the most powerful nation but he observes that, foreign policy attention is focused predominantly on Eurasia. The USA’s world politics can be understood as a “high precision compass that tracks this center of gravity and adopts its foreign policy accordingly” (p. 260). With “center” he means the global economy’s center of gravity. He notes how this center of gravity moves (p. 260):

In the three decades after 1945, this center of gravity was located somewhere in the middle of the Atlantic, reflecting how Europe and North America dominated the world’s economy. By the turn of the century, however, this point has shifted so much that it was now located east of the borders of the European Union. Between ten years we should find it east of the border between Europe and Asia, and by the middle of this century, most likely somewhere between India and China.

So even though the USA is the dominating power with regard to technology, military, and economy, it is just one more player on the Eurasian Continent where the action is and where the fate of the world is determined.

Thus, what Maçães means with the dawn of Eurasia is not an emerging superpower, but a theater of a diverse set of actors, which will not converge or adopt each others culture and world view anytime soon, but are nonetheless bound to each other by a common geography, a common economic space, and a shared communication infrastructure. Certainly, Maçães has a point and it is worth to keep an eye on Eurasia.

(AJ May 2020)